How Segregation, Racism, and Fear Kept an Entire Community from the Water

For many, summer is the perfect time to hit the beaches and pools for family vacations. It’s time to swim laps or to jump into cool water during the hottest days. However, statistics about water safety reveal this is not a pastime that’s equally enjoyable and safe for all children. According to this report, black children (ages five to nineteen) are five and a half times more likely to drown than their white peers.

Here’s a look at the factors that contribute to that fact and how you and your family can take your safety into your own hands.

Legalized Segregation

The first important thing to understand about the black community and water is that it hasn’t always been a contentious relationship.

“During the 19th century, people of African ancestry were more accomplished swimmers than people of European ancestry. They were more likely to be swimmers and more likely to be better swimmers,” said University of Montana professor Jeff Wiltse, author of Contested Waters.

As this article illustrates, the issues began with Jim Crow segregation (starting 1877) and were exacerbated throughout the twentieth century.

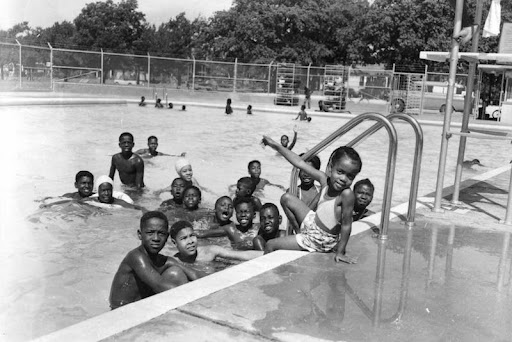

In the 1920s and 1930s, thousands of swimming pools were built throughout the United States. With the lack of air-conditioning, pools were a popular way to beat the heat. Segregation, however, ensured these pools were predominantly for whites only.

Photo Credit: USA Today

Any pools that did exist for the black community were often smaller, less maintained, and generally less desirable.

Photo Credit: Texas Standard

Photo Credit: Texas Standard

This legally sanctioned segregation was the first step to shutting out the black community from recreational or competitive swimming.

Swim Clubs, Gated Communities, and Backlash: Getting around the Law

The Civil Rights Act was enacted July 2, 1964. This ostensibly ended segregation, but even with the legal abolishment of Jim Crow laws, the black community was still systematically excluded from swimming.

In some cases, it was overt and violent. Riots erupted in Baltimore; Los Angeles; St. Louis; and Washington, DC, pools. In other towns, white swimmers threw nails, bleach, and acid into the pool to deter black swimmers. Despite the legal changes, African American swimmers still routinely feared for their safety at desegregated pools.

In other instances, white communities got around the law in subtler ways. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, tens of thousands of private swim clubs emerged throughout the United States. Using the framework of membership requirements or gated access to communities, these were, for all intents and purposes, whites-only pools.

Similarly, white swimmers would also refuse to frequent desegregated pools, which led to many of those facilities shutting down.

From the aversion to interracial relationships to unfounded, prejudiced fears of black swimmers passing on communicable diseases through the water, there were numerous reasons white swimmers shut out black swimmers.

The end result, however, was decades upon decades of stunted access to swimming for the African American community and an inability for a vibrant swimming culture to take root.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

After more than a century of being denied free and open access to water, the effects are tangible throughout the African American community.

According to this national study conducted jointly by the University of Memphis and the USA Swimming Foundation, 64 percent of black children cannot swim. That’s compared to only 40 percent of their Caucasian peers.

Additionally, if a parent cannot swim, his or her child only has a 13 percent chance of learning the essential survival skill. When a parent either actively or unintentionally discourages water activities, that sentiment gets passed on to the child, and this cycle continues.

“Swimming doesn’t get passed down from one generation to the next. And instead, what has gotten passed down is actually a fear of water,” said Wiltse.

All these factors contribute to this stark underlying statistic: “…black children are, depending on their age, three to five times more likely to drown than white children.”

It’s Never Too Late

Swimming is an essential survival skill. The good news here is that it’s never too late to learn how to swim!

Take Patricia Mathison of Louisville. She learned to swim at fifty, describing the experience as the most “liberating thing” she’d ever done for herself.

If you want that experience for yourself or your child, enroll now.

We offer infant swim lessons for children six months to four years, one-on-one Learn-To-Swim lessons for anyone four years or older, and Young Masters swim team lessons at select locations.