WeAquatics Owner David Worrell Provides His Insight

Anyone who has ever tried to coach or to teach young children knows how challenging it can be. With twenty years of general swim coaching experience and ten years specifically dedicated to teaching children from six months to four years old, David Worrell, the proud owner of WeAquatics in Washington, DC, is uniquely aware of both the rewards and difficulties of teaching swimming to very young individuals.

Whether you’re thinking about putting your young child into swim lessons or you’re a new instructor yourself, David outlines three crucial but often overlooked points that can make or break a swim lesson:

Soft Skills: The Undiscussed Element of Teaching Swimming to Children

Before we dive into the three points, it’s important to explain what this article will tackle. The Internet already has a wealth of information about how to administer swimming lessons. It discusses when to have students float on their backs, when to introduce streamlined kicking, and so on. This article, however, is about the often-overlooked aspect of how swim instructors should conduct themselves during lessons to help ensure success. It’s about the necessary soft skills, communication styles, and self-management tactics needed to pace and to conduct a lesson with a very young swimmer.

Point #1: Know Who You’re Teaching

The first crucial point many swim instructors overlook is that you have to know who you’re teaching and understand what’s reasonable to expect. If, for example, you’re providing swim lessons to a child under three years of age, you’re simply not going to get a lot of coordinated leg or arm movements. If you go down the road of trying to achieve that, it’s a recipe for a frustrated student and a disappointed instructor. For students of this age group, once they’re propelling themselves through the water in any capacity, that’s about as much as an instructor can ask.

This awareness is also important when it comes to communication. The way you administer an adult swim lesson is fundamentally different than how you work with an infant or toddler, and that largely comes down to the two groups communicating in very different ways.

Again, failing to appreciate what’s reasonable to get out of a given student can quickly derail what could have otherwise been a productive swim lesson.

Point #2: Don’t Move Too Fast Too Soon

Another common mistake many swim instructors make is trying to do too much too soon, and rather than productively pushing the student, it ends up being counterproductive.

Aim for Incremental Progress

When working with very young children, instructors have to be especially particular about what skills they’re developing. You want to ensure each lesson is set up such that you get incremental progress throughout the course of instruction. Never move from one step to the next without linking concepts and lessons. If the gap from one skill to the next is too wide or if you jump erratically from one concept to the next, that’s when a young student gets confused, and confusion, more often than not, leads to unproductive resistance.

Short, Frequent Lessons Are Key

For young children, success in the pool comes from muscle memory, not verbal cues. This is why short but frequent lessons are so much more effective with young swimmers. Don’t expect to spend an uninterrupted hour or even half-hour in the pool with a young child. Lessons should typically occur as a series over the course of the week and last no more than eight to twelve minutes. This is how young students learn. Whether you’re an instructor or a parent, this is what to expect in terms of schedule.

Minimize Distractions and Detractors

Short lessons allow for the development of that crucial muscle memory, but they also help ensure the student can stay focused for the entirety of the lesson. Too much time in the pool at once often leads to a young student getting distracted, reacting adversely to the water temperature, or getting overly tired.

Be Aware of a Student’s Comfort Level

With swimming lessons for young children, you’re taking students from land (a place of comfort) to the water (somewhere they likely have little experience). For very young children, they might even still be getting their bearings on dry land, so the transition to water can be especially disorienting and upsetting.

Even a child who greatly enjoys bath time might be unhappy in a pool, and instructors and parents alike should be prepared for that. The water is cooler, there’s nothing to hold onto, and it’s common for a bit of water to get into the student’s nose or eyes. In all these ways, you’re removing a young student from a place of comfort. Even if that student becomes upset, the lessons can still be effective. The instructor just needs to read each reaction for what it is and respond appropriately in order to teach a student through that discomfort.

Let the Child’s Progress Lead

With students so young, instructors and parents can’t expect to follow a set schedule. There’s a progression of skills, but before moving to the next element, the instructor needs to wait for the student to show either some sign of mastery or an anticipation of what comes next when an instructor sets up a particular scenario. Mastery or proper anticipation could take anywhere from one lesson to a series of lessons. It depends on the student and his or her comfort level with that particular skill. The younger the student, the more particular the instructor has to be about managing the pace of the lessons and making sure that each time a skill is practiced, the experience of that particular skill can be memorized by the muscles. If each practice attempt feels different, it will take longer for the student to master the skills.

Have Realistic Expectations

When dealing with this age group, parents and instructors shouldn’t be expecting improvement in leaps and bounds all the time. If a child is extremely upset on day one and that crying is a bit calmer on day two, then you know you’re working in the right direction, and the student is getting a feel for what the instructor is trying to do. That small improvement can constitute the entire day’s progress, and that’s OK. If you come in with an agenda, you’re almost always going to be disappointed and frustrated. Trust that in the long run, short, frequent lessons will help manifest those swimming skills. Just as it took time for the child to learn to walk, learning to swim will also take time, and having realistic expectations can make it easier for everyone.

Point #3: Be Mindful of Your Nonverbal Cues

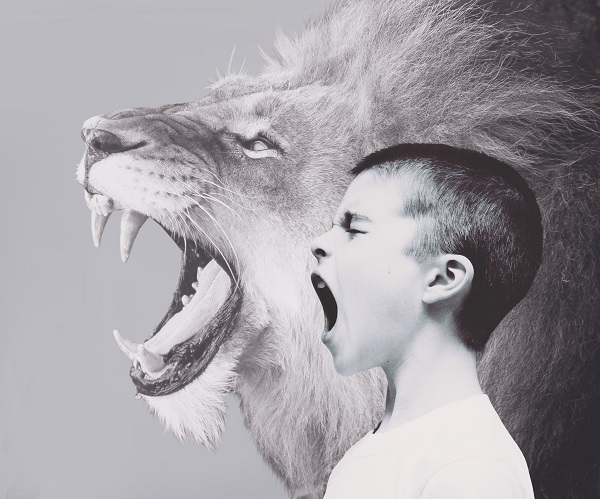

When working with this age group, it’s less about what you say and more about your body language and the totality of your nonverbal cues. (It’s not just about coaches either. As swimmers get older, body language is important for them too!)

Establish Trust with the Student

In everything you do, from how you hold a student in the water to what you do with your face and hands when that student gets upset, you must communicate safety and confidence. This is how you get a student to trust you, and from the instructor’s standpoint, this is how you get parents or caregivers to trust you. Without trust and you being absolutely predictable and steady throughout the lessons, students are never going to let you take them outside their comfort zones. Instead, they’re going to get upset, which is only going to make it harder for you to stay focused on what you’re attempting to do.

Based on the student’s age and experience level, you can adjust your hold while still communicating safety. With a very young swimmer, for example, you won’t let any water get in his or her face at first because you’re establishing that being held equals safety. The student might be uncomfortable, but he or she should feel safe. Establish this first, and work from there.

Don’t Take Tantrums Personally

If you have young children or if you’ve ever worked with them, you’re probably no stranger to tantrums. The key is to stay calm when the student gets upset—no matter how hard that might be! Remember that what the student is reacting to is simply being in an unfamiliar situation. It’s not about you, so don’t take it personally. Let each individual student guide the pace of his or her lessons, and let the student’s body language and reactions determine what you need to do to soothe him or her and to keep the lesson moving forward.

Keep Calm. Always.

Always be aware of what your body language is projecting to the student. If a young swimmer becomes upset or uncomfortable, and you get upset or allow your actions to become less deliberate or controlled, you’re just confirming for the student that he or she should be upset. Always be calm and collected throughout a lesson, and minimize any unnecessary movements.

Prepare for the War of the Wills

Sometimes students are going to be upset in a way that simply makes no sense. You’re not trying to float, to grab the wall, or to do anything, but the child is inconsolable. Usually this is a student testing how upset he or she can get before you or Mom or Dad ends the lesson. This is the dreaded “war of the wills.” The student wants to see who will break first, and in this game, whoever breaks first loses.

If you give in and end the lesson early, you’re just training that student to do this every time he or she doesn’t want to participate in a lesson. In these instances, it’s even more important to stay and to convey calm. You might get very little to nothing done that day, but don’t end the lesson early.

Don’t Be Too Quick to Pick Them Up

Just because a student is crying doesn’t mean you have to pick them up immediately. Stopping what you’re working on to comfort them can actually be counterproductive in the greater scheme. Understandably, this can be the hardest line for instructors to walk, but as long as you’re holding students safely and securely and you’re conveying calm through your touch and body language, you don’t have to rush to pick them up. Not drawing too much attention to the tantrum communicates to the student that he or she doesn’t have to be upset just because the water is cold or there’s a bit of water in his or her eyes or nose.

It all boils down to making teachable moments so young ones learn from what they experience in the water. No lesson is perfect, but there’s an opportunity in each lesson for a student to learn something. A strong swimmer is one who can apply what he or she knows to different scenarios while remaining relatively calm.

Interested in learning more about our classes for young children? Read all about them here.